50 years ago, an immense tsunami would change the life of Hula forever.

50 years ago, an immense tsunami would change the life of Hula forever.

The 35-foot waves of the 1960 tsunami bent parking meters to the ground and wiped away many buildings in the city of Hilo on the Big Island of Hawai’i. 61 people died, and Hilo’s economy was crushed.

Four years later, in 1964, Hilo was still suffering economically. The tsunami’s aftermath of destruction plus the slow decline of the Hāmākua coast sugar cane factories, created a bleak future for Hilo and the Big Island.

Something needed to change.

Helene Hale was the Big Island’s Executive Officer (now called a mayor), and she had a vision for the island’s recovery. She knew she had to do something which would bring visitors back to Hilo town and the Big Island.

During her research, she heard of a 3-day, yearly event on Maui called The Lahaina Whaling Spree. She was curious about it. So, she sent a committee to Maui to see what was happening there.

The Lahaina Whaling Spree brought people from all over the islands and, eventually, the mainland. This three-day event was created to celebrate the time when Lahaina was a significant port for whaling ships.

The three days were filled with entertainment, contests, and a parade.

The Hilo committee returned from Maui, excited to report their findings and suggestions. What is the result? In 1964, a festival in Hilo was born. The birth of this festival was created primarily for the economy of Hilo. It proved to be history in the making.

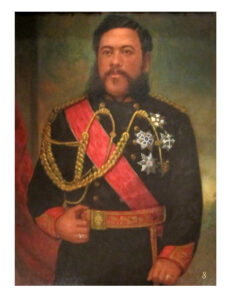

The festival was named in honor of Hawaii’s King, David La’amea Kalākaua, affectionately known as, The Merrie Monarch.

King Kalākaua was fun-loving, flamboyant, and a huge patron of the arts. He was especially fond of music, Hula, and the native language. The King continuously fostered the first Hawaiian cultural renaissance during his 17-year reign. He even broke protocol at his 1883 coronation by including Hula Performances as part of the celebrations.

Primarily, King Kalākaua brought back the Hula after influential Christian Missionaries in the government had repressed it. And bring it back, he did! Hence, he received the nickname the Merrie Monarch, and Hilo town’s Hula festival was named after him!

Initially, the Merrie Monarch festivals took off like gangbusters. They included events such as:

- King Kalākaua beard look-alike contest

- Barbershop quartet contest

- Relay races

- The re-creation of King Kalākaua’s coronation

- A Holokū (Hawaiian dress with a long train) Ball

By 1968 however, after 4 yearly festivals, interest and participation in the original Merrie Monarch Festival was waning.

Enter Aunty Dottie Thompson.

Aunty Dottie changed the face of The Merrie Monarch Festival. She set out to illuminate the goals and objectives that more closely reflected the ideals of King Kalākaua. He had sought to uplift and rekindle the pride Hawaiian people had for the Hawaiian culture. She wanted to continue that celebration of the Hawaiian Culture by making it the festival’s focus.

This new Merrie Monarch Festival would bring the best hula dancers from all the islands to represent the Hawaiian mastery of Hula. It would be a rite of passage, a celebration, a proclamation, and a source of immense pride in the Hawaiian culture and the Hawaiian Nation.

“Hula is the Language of the Heart. Therefore the Heartbeat of the Hawaiian People.”

– Kalākaua Rex (King Kalākaua)

From that point on, every year, the festival grew. Three years after Aunty Dottie took the reins, at the suggestion of 3 very influential Kumu Hula (hula teachers), a competition was created. In the first year of the competition, 9 hālau (hula school) of wahine (women) entered.

Now, fifty years later, there can be up to 30 hālau of men and women participating.

These days, there are 3 nights of competition:

- First Night: Miss Aloha Hula – a single female dancer that chants and dances both kahiko and ‘auwana

- Second Night: Hula Kahiko – where hālau men or women dance ancient Hula in groups (dance, chant, or inspiration originating before 1893)

- Third Night: Hula ‘Auwana – where hālau of men or women dance modern Hula in groups

The festival continued to expand. In 1980, Aunty Dottie began televising the event so the kupuna (elders) who could not attend would still be able to watch.

As the popularity grew, the festivities increased to a week-long event. This included a large juried craft fair consisting of made-in-Hawai’i goods, a parade, and a Wednesday night Ho’ike (come and see) where everyone is invited to come and see many Hālau and Hula Dancers perform.

People flocked to Hilo during this Merrie Monarch week. Some for a day to shop at the craft fair. Others for the weekend to see the competition. Many came for the whole week and enjoyed this lively coastal town. Tickets needed to be reserved months in advance.

2020 brought sad news to Hilo like many places in the world.

For the first time since its inception, The Merrie Monarch was canceled a month before it was supposed to be held in 2020, due to the pandemic. People around the world had given their sweat and tears in preparation for this once-in-a-lifetime event. The dancers and musicians were devastated.

Each hālau prepares up to 12 months and comes from various places in the world to watch or participate. Crafters count on this big event as a primary income source for the entire year.

In the final weeks of preparation for the hula competition, the bonding within the hālau is intensified. The dancers begin to practice daily with their musicians. They prepare their costumes and lei. All members live and breathe for the festival as one entity. It has been their focus for months. Everyone had to take a deep breath and, through a lot of tears, they had to let it all go for 2020.

In 2021, with a lot of planning, The Merrie Monarch Festival went on, Virtually.

The organizers and sponsors worked hard to find a way to not cancel again. There were only 15 hālau. And, there will be no parade or craft fair.

The Merrie Monarch festival has sold out for over 25 years. Once again, this year it will carry on as before.

The organizers were clear: “while the perpetuation of hula and Hawaiian culture is our mission, our priority during these unprecedented times is keeping our ʻohana and community safe and healthy.”

Although it was canceled one year and a small, virtual event the next, there is one thing we do know: the perpetuation of Hula and the Hawaiian culture will carry on. The Merrie Monarch Festival is back again, in all its glory since then.

In the meantime, here is a glimpse of the all the winners from 2019. Above are the over-all wahine winners. Take a moment and click below to feel and see a breathtaking and thrilling sight.

2019 Winners of The Merry Monarch Hula Festival

We look forward to sharing more with you about the true Merrie Monarch – King Kalākaua. His story is an undeniable reflection of Hawai’i, and its culture.

Writing and Graphic Design by Sugandha Ferro Black

Photos courtesy of paid for or free sources unless otherwise noted.

Winners and Stadium | CC BY-SA 4.0 Allanbcool/Flickr, Male ‘Auwana Dancers, ‘Auwana Dancer in White, Male Kahiko Dancer | CC BY-SA 2.0 Thomas Tunsch/Flickr, Title Image-Hilo Bay | CC BY-SA 3.0 Kanoa Withington/Wiki, Hilo Bay to the Mountain | CC BY 2.0/Eric Tessmer/Flickr